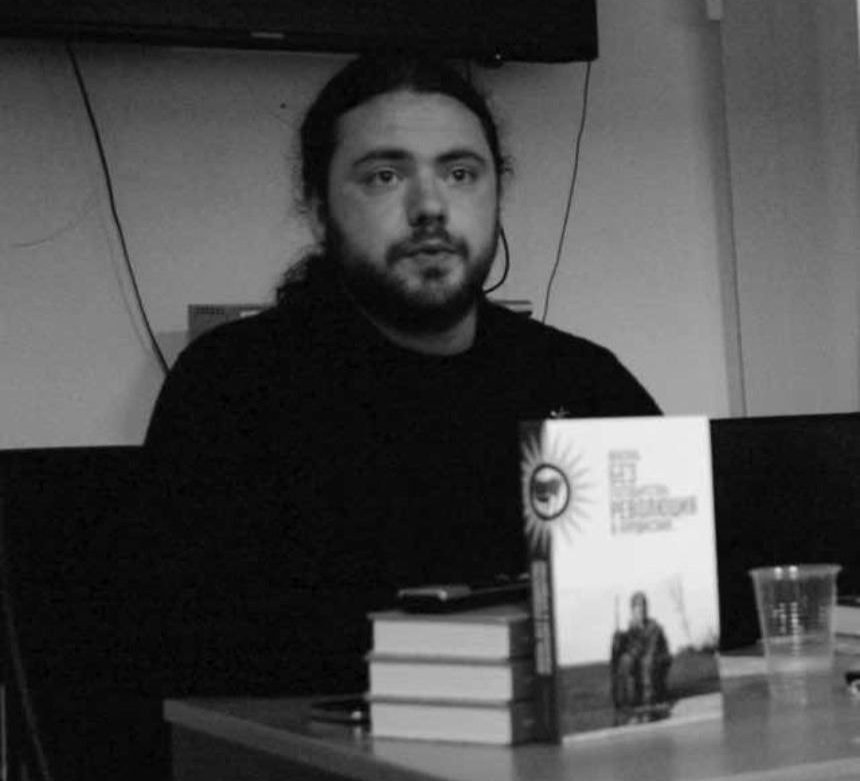

A Leshy friend

A month ago, Dmitry Petrov, a Russian ultra-left activist nicknamed Ilya Leshy, died near Bakhmut. His friends recall how he ended up in the war and what he died for

Exactly one month ago, on April 19, in the hottest spot of Ukraine, near

Bakhmut, died Russian anarchist Dmitry Petrov, a researcher at the Institute of African Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, PhD in history, author of several books about the liberation movement in Kurdistan. Dmitry was one of the founders of the Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists, which took part in the war on the Ukrainian side. He was not a “media” representative of anarchists in Russia (like, for example, Alexei “Socrates” Sutuga, who died in a fight on September 1, 2020, or other well-known figures). Those who were familiar with the Russian anarchist movement of the late noughties may remember him under the nickname “Ecologist.”

Already after his death, comrades of the deceased Petrov publicized information that he had been active in guerrilla activities in Russia since the late noughties. He took part in the actions of the Black Bloc – the burning of the DSS point and other direct action actions, for which no one was ever punished. At the same time, Dmitry himself was in Russia until 2018, combining urban gerilla with scientific activity. During this time, he managed to write several books, participate in the Moscow protests on Bolotnaya (2011-2012), in the Maidan revolution (2014), in the protests in Belarus (2021), and visit the Kurdish revolutionaries in Rojava (2015-2019).

I met Dima at the beginning of the tenth century at a humanitarian history event in Voronezh. I was giving a lecture on urban guerrillas in postwar Europe, and Dima flooded me with questions. A man with an encyclopedic knowledge of everything, he himself was an excellent lecturer, deeply immersed in the topics he was passionate about: history, anarchism, nature.

Dima was a convinced anarchist. And, no matter how pathetic it sounds, he made a huge contribution to the development of the anarchist movement in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

He became interested in anarchism when he was still at school, and together with his comrades they published an anarchist newspaper “Heretic”.

Once long ago in an interview he told me that in his childhood he was strongly influenced by his father’s stories about the Makhnovist movement during the Russian Civil War. His father also brought him for the first time to the Falanster store (the oldest independent bookstore in Moscow), where Dima got his hands on the Autonomy magazine. “My first acquaintance with the movement was participation in the “Bespartschool” – a rather interesting circle of lectures and discussions held many years ago at the Jerry Rubin Club in Moscow. From the age of fifteen I began to actively interact with the organization of “revolutionary anarcho-syndicalists”, writing articles for their samizdat,” Dima later recalled.

A little later, the first protests began. Since the mid-noughties, he has been actively involved in the fight against point development, in various animal protection activities, and in environmental protection. For his environmental activities, he received his nickname Ecologist.

Nature in general was for him the most important component in his life on a par with anarchism. He had dozens of ethnographic expeditions and trips to remote parts of Russia. He could tell about every nook and cranny of Moscow, and there was probably not a museum in the capital or the region that he had not visited.

One more thing that surprised me when I met him: the Ecologist was a pagan. Moreover, he practiced Slavic paganism, which in those days was absolute nonsense among antifa and the leftist movement.

“Monopoly” on paganism was then in the hands of the ultra-right, among nationalists it was commonplace.

At the same time, in the late noughties, he created and promoted the site Pagan Antifa, which published materials about eco-anarchism, primitivism, paganism, and thematic music. I remember well how the far-right was triggered by this project: they couldn’t understand why antifascists were “encroaching” on their culture, and wrote angry comments on the site’s forum.

At the same time, in the late noughties, he created and promoted the site Pagan Antifa, which published materials about eco-anarchism, primitivism, paganism, and thematic music. I remember well how the far-right at that time was triggered by this project: they could not understand why antifascists were “encroaching” on their culture, and wrote angry comments on the site’s forum.

The environmentalist was not shy about identifying himself as Russian; he never avoided it. Even while in Ukraine, he always emphasized that he was a Russian who was defending Ukraine’s freedom from Putin’s invasion. The connection to the Motherland was very strong for him, and this can be seen in some of his last interviews. In his suicide letter he emphasized: all nations have the same woe – greedy and power-hungry rulers.

He was not a nationalist; he despised all chauvinism and imperialism. At the end of the noughties, he was an active member of the nascent antifa movement in Moscow. At that time, violence on the part of the far-right was reaching its peak. Numerous neo-Nazi attacks on migrants and informals provoked spontaneous self-organizing groups of young people to repel the ultra-right by force. Dima was a member of Ivan “Kostolom” Khutorsky’s so-called “mob” (power group): they defended concerts and lectures from neo-Nazi attacks (to be fair, they later attacked them themselves). In November 2009, Ivan Khutorskoy was shot dead in his entryway by a far-right militant from the “BORN” gang. Before that, on January 19, 2009, anarchist and Novaya Gazeta journalist Anastasia Baburova and lawyer Stanislav Markelov were murdered. The murders were committed by the neo-Nazi group “BORN”, linked to the nationalist organization “Russian Image”. The latter were accused of links to the Kremlin.

Despite this dangerous rhythm of life, Dima Ekolog managed to be active without getting caught in the System’s millstones. He took part in all the “Bolotnaya” protests in Moscow, and the “hottest” period of the Maidan in Kiev he met in a tent city. Later there was Rojava in Syria, where Dmitry studied the egalitarian community of Kurdish guerrillas. At the same time, he had time to write books, scientific articles, and defended his PhD thesis on “Sacral geography of the eastern districts of the Arkhangelsk region”.

In 2018, the anarchist movement in Russia was subjected to severe repression, the “Network” case began (anarchists from St. Petersburg and Penza were accused of creating a terrorist group to overthrow the state system, all were found guilty, terms from 5 to 18 years) – several “terrorist” cases with a dozen detainees, the explosion of anarchist Zhlobitsky in the building of the Arkhangelsk FSB. Now the security forces were interested in Dima: he learned about it from his sources while he was in Kurdistan, and made a hard decision not to return to Russia.

Later, his place of residence was searched. The Ecologist settled in Kiev, where he continued his activist and scientific activities. Then the war broke out.

But Ecologist did not join the resistance to Putin’s regime on February 24, 2022, but much earlier. Already after his death, it became known that he had been actively involved in a number of guerrilla groups since the late noughties. “People’s Retribution”, “ForNurgaliyev”, “Anti-Nashist Action”. – these groups had different names but similar activities. They set fire to police stations, police cars, military recruitment offices (they were always an important target for anarchists, long before the war started). One of the most notorious guerrilla actions of those years was the bombing of a traffic police post at the 22nd kilometer of the Moscow Ring Road on June 7, 2011. Responsibility was claimed by a certain “Anarchist gerilla”, law enforcers never found these mysterious bombers. As it turned out, Dmitry was directly involved in this action. The Black Blog project, created to cover the city’s gerilla, became a platform for publishing actions of “people’s retaliation”. The Ecologist was also directly involved in its creation. Over the course of several years, anarchist guerrillas committed more than a hundred (according to the Black Blog website archive) arson attacks on police stations and cars, military commissions, cars of government officials, and construction equipment designed to destroy forests. In 2019, the project officially came to an end.

Dmitriy carried out underground activities even after leaving Russia: both during the protests in Belarus and in Kiev. To take part in the protests in Belarus, he illegally crossed the Ukrainian border. There he participated in self-organization of anarchists, direct action actions and fights with law enforcers.

Despite such a colossal activist experience and loyalty to his ideological principles, Dima Ekolog was not detached from reality, in life he was quite an ordinary guy, educated, intelligent and charismatic. Communicating with him, one could not even think that at night this man was throwing Molotov cocktails at government offices. The soul of the company, with him it was possible to drink, and to talk and discuss. The comrades with whom Dmitriy once corporatized remember him as a loyal and reliable colleague who, again, forgive the pathos, thought first of all about the team, and then about himself.

“Once we were wandering at night through the autumn forest, disabling construction equipment,” recalls Svyatoslav Rechkalov, a political refugee in the case of the anarchist organization People’s Self-Defense. – And one girl lost her sneaker. She simply stepped on the ground, and it swallowed her foot. The foot was pulled out, but the shoe remained somewhere underground. Well, Dima took off his shoes, gave her his sneakers, put bags on her feet and went like that.

I looked at him and asked, “Aren’t you cold? Do you want to switch after a while? He said, “If you get too cold, then we’ll switch. But he ended up wearing the bags all night. That’s how he was.”

Dima Petrov was from an academic family, a modest Moscow intelligentsia, his father was a writer. Dima himself connected his professional life with science. He was an employee of the Institute of Africa of the Russian Academy of Sciences, before that he worked in museums and practiced journalism (he was a correspondent at the Agency for Social Information).

“I was always amazed how he had time to do scientific research on the topic of the Russian North, the study of the Kurdish social experiment with direct democracy in the Middle East and a bunch of other things,” recalls Dmitry Okrest, journalist, author of the podcast “Public Appeals” and co-author of several books by Dima Petrov about Kurdistan. – He always approached the preparation of texts carefully and carefully, he did not want to do a sloppy job and did not pull the blanket over himself. His strong point was that he did not look for reasons and occasions for conflicts, but on the contrary, he always tried to avoid them. He understood very well the importance of communication: the fact that people can be emotional, people can make mistakes, and if an argument is not escalated, things can be fine. Yes, we argued more than once about books, how and what to publish, we had different approaches. I wanted a less politicized read with a more journalistic narrative. But we always found compromises. I heard similar stories from other people who worked with him. We hadn’t seen him in person for a long time and hadn’t communicated much in recent years, living in different countries. Again, I accidentally learned that Dima was at the front when I was preparing an episode of my podcast about the anti-fascist movement. Dima never liked to talk about himself. Others might have already taken thousands of selfies from the front, but not Dima. And this reluctance to be proud certainly says a lot about him, about what he was like.”

His keen sense of justice and faith in the idea did not stop any borders or police batons. And even the fear of death could not stop him. After the war began, Dima became a volunteer and then joined the territorial defense. He and his comrades organized an “anti-authoritarian platoon” as an independent unit within the TRO forces. But after a series of bureaucratic problems, their platoon was disbanded after some time, and Ecologist began looking for opportunities to get to the front lines. After long and persistent attempts to get to the front, he managed to do so. He took part in the liberation of a number of occupied territories. Dima Ekolog died under artillery fire, performing a combat task near Bakhmut, surrounded by his comrades – foreign volunteers, anarchists Cooper Andrews and Finbar Kafferka, who also died.

Dima Petrov (Ecologist, Ilya Leshy, Phil Kuznetsov – his pseudonyms from different years) was a historian, and now he had a chance to write history himself. He took it.

He was 34 years old.

Veniamin Volin

This interview was recorded in February 2023 by Dmitry Okrest, author of the audio podcast about the history of antifascism “Public Appeals”. The text version has not been published. With the author’s permission we present fragments of this conversation.

In Russia, more than a dozen anti-fascists and anarchists died at the hands of the Nazis. More than 60 people suffered from repression. In Belarus, more than 30 activists are currently in prison. In Ukraine, five people from the movement were killed in the past year. Since February 2020, the Russian state has had a monopoly claim on anti-fascism, fighting in Ukraine under monotonous talk of denazification.

Ilya Leshy, a political refugee from Russia who fled the country because of repression and is now at the front, and journalist Sergei Movchan talk about what happened between February 22nd and February 23rd. He is a member of the Solidarity Collective (originally called Operation Solidarity), a volunteer network busy supporting volunteers and civilians.

Movchan:

—It seems to me that recollections of the first day of the war —are already a certain genre. It is the starting point for quite a lot of conversations between people. Intimate communication can be set up by discussing this very first day.

For me, the day began with a phone call. At 5:00 I received a call from a friend of mine in the Kherson region. I dropped, and then I realize that it was not just for a reason that the call was at 5:00, and I call back. He said it had started. So I woke up. I woke up my friend, I said, “Here we go.” One word that explains everything. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a plan at the time, I didn’t have a backpack.

But I watched on the streets as cars were pulling off, people were packing, everyone was flying somewhere. And parallel to that, other people were walking their dogs smoothly.

Leshy:

—The relatives called very early in the morning at a time when they don’t usually call. And at that moment it became clear that a very extraordinary story was going on. Well, of course, we were all waiting to see if it might happen, although we hoped it wouldn’t. We didn’t believe it until the last moment.

— What does your typical day look like today?

Leshy:

—There’s no freedom of movement here. There is a rather strict regime of military control, and in general a Spartan regime: here we do our laundry by hand. Everything that in ordinary civilian life, in the metropolis, machines do for us, here we do with our own hands. The thesis that my revolutionary comrades from Rozhava used to say is confirmed. According to them, any military path —is only a few percent of the time when you are actually in combat. The rest —is waiting and solving domestic and logistical problems.

— What does the team do now?

Movchan:

— Even two or three weeks before the invasion, possible actions were discussed, and it was decided that two such entities would be created: a military entity (people would go into territorial defense) and a volunteer entity (should provide the people who would take up arms with everything they needed).

The organization started as a volunteer initiative that helps the fighters of the anarchist movement at the front. At the very beginning, we really tried to look for the most necessary things, because there was nothing at all in Ukraine. In the first days even bandages could not be bought in the pharmacy and we had to get almost everything from Europe and bring it thanks to our comrades from Poland, Germany, France and other countries. But over time, of course, our organization grew.

The number of people we started to help also grew, and from a certain point we started humanitarian trips — once a month is mandatory.

Leshy:

— In the first couple of days, I concentrated on media work. From February to the end of July, I called journalists and gave comments through comrades. Again, out of our initiative, people started collecting help — volunteer and humanitarian. And from the very first day, some of our comrades went to the territorial defense of the Kiev region. We had an agreement with our friend officer Yan Samoilenko, who, unfortunately, has already died.

Jan was a lieutenant, the organizer of his group. We met about a month before the war. He was an old anti-fascist from the Arsenal soccer club (the fans of this Kiev club were known for their anti-fascist stance) and had worked in the security services for quite a long time: he thought it was important that the [anti-fascist] movement had an outlet for these structures. This is a very unorthodox position for us, but one that has more than justified itself in the current circumstances. He had a broad strategic thinking, which, again, unfortunately, is not always characteristic of our brethren.

In 2014, when there was a similar challenge (there was an attempt to gather an anarchist hundred on Maidan, which was supposed to consist of activists from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. The attempt was thwarted by the efforts of right-wing radicals), comrades took part in small groups in separate units. On the eve of this war, we wanted to do something more organized, which could become a structural component of the movement itself.

Even before the full-scale invasion began, Ian invited us to training sessions. What set us apart from neighboring units was that we did intensive training and basic basic basic military training – it was part of our self-organization.

People from neighboring units asked if there was any way to join us, because they saw that we were quite organized and active.

The group was dominated by comrades from Ukraine, but there were also people from Belarus and Russia. We put out a call to the world anarchist community – several comrades from Western countries came, including people with experience of participation in the revolution in Rojava. These people became our main instructors.

— Why did a separate military formation of anarchists and anti-fascists cease to exist?

Movchan:

In fact, for a very long time the command flatly refused to transfer the detachment to the combat zone. At some point, people in small companies began to do it on their own, as they did not want to sit in the rear.

For some in the detachment, the number one issue — wasis to fight back against the Russian army. In principle, that’s all. For others, the important question is: “What kind of Ukraine are we fighting for? And what should be after this war?”. We also faced a rather classic problem of the conflict between authoritarianism and efficiency. People who do a lot try to do everything and control everyone. They start to think that everything lies on them, so they have the right to decide more than others.

Leshy:

—Command orders were carried out, but we discussed many issues— there was always freedom to criticize. It was even institutionalized: the deputy squad leader would collect criticism and pass it on. Some of the problems were due to the fact that our community is small and in one company there were people who had old scores to settle — there’s no getting away from it. Plus the habit of not listening to any authority figures. But in general, people showed pro<per understanding and respect if the manager had a lot of experience and was in a leadership position for a reason.

— What specifically needs to be done in terms of squad provisioning?

Movchan:

— From socks to drones to cars. About 150 people from the left-wing anti-authoritarian movement, whom we help more or less regularly. We also started actively cooperating with trade unions and started helping members of the trade union movement.

Leshy:

— It is on the shoulders of civil society and volunteers to provide radios, thermal imaging cameras, night vision devices, drones, mats, sleeping bags, and body armor.

— In the leadership of Azov there were originally known Russian and Ukrainian Nazis, something that few people like to remember. But there were quite a few investigative texts about it, for example, which are declared foreign agents in Russia for other things. Now Azov has been expanded to a brigade. And do you feel some kind of right-wing hegemony, which Russian propagandists so often talk about?

Leshy:

— It is clear that this is a wide spectrum: there are followers of Stepan Bandera, and there are outright Nazis. Yes, they are visible, but they do not dominate the army. To say that there are Nazis all over the place, — it’s pure propaganda. But at the same time, we cannot say that these people do not exist at all and that it is all a fabrication of the Kremlin. As a Russian, I certainly feel tensions, for example, in teams with my fellow Ukrainians.

Movchan:

There is no hegemony of the ultra-right in the army now. Even more, in 2014 their role was rather even more prominent, because then the volunteer battalions played a very important role in society. They were looked upon as the main heroes. And the far-right played not the least role there: they came out victorious and scored a huge number of political points. After 2014, they created parties and civic organizations.

Virtually all the far-right has now, indeed, gone to the front, but they have no monopoly on speaking out in this war. Everyone now has fighters — right-wingers, left-wingers, liberals, LGBT, feminists.

But there has been a normalization of Ukrainian nationalism, which is no longer absolutely problematic. Thanks to Putin: Bandera has turned into a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. But no one is interested in who the real Bandera was, what he did and who he was. People argue as follows: “Bandera — is a figure that pisses off Putin and Russians, so this is our hero.” Or here’s a black and red flag — no longer matters what happened underneath it in the mid-twentieth century. It’s exactly the same symbol of our resistance. It’s worn by anyone. Including people who are usually associated with progressive views. The existence of the “Queer Banderites” — is an indicative thing, which is absolutely real in modern Ukraine. That is, nationalism is normal, but at the same time there is no hegemony of the ultra-right. And even more I will say, they feel this problem. If you go to right-wing information resources now (Nazi ones especially), they are worried that when they return from the front, Ukraine will not be the way they would like it to be.

— Many people I know after 2014 began to use exclusively Ukrainian in their everyday life. Many media outlets abandoned bilingualism in their publications after February. In general, how much has the attitude towards Russia and the Russian language changed?

Movchan:

— The question Ukrainians put to Russians is: “Why aren’t you overthrowing Putin?” It turns out to be a collective responsibility. Ukrainians are wondering why so many people support him and where are the anti-war protests. A huge number of people in Ukraine actually thought that when the invasion started, it would cause internal destabilization in Russia. Has that been lost? Have all the bridges been burned? I would say probably not. But the level of hatred towards Russians is extremely high — it’s never happened before. But I guess there’s still a chance. With a change of regime, perhaps something could change.

Leshy:

to everyone as a people. In short, the attitude, of course, has become very complicated. It has naturally become more tense and worse. But, again, I believe and hope that it can still be corrected. But for this, of course, Russians need to prove themselves as a historical community. If you are not slaves, if you are not in favor of Bucha and Izyum (the most famous cities for the execution of civilians), then what, in fact, what can you say to us in response? This is a very difficult question.

What is it like to be a Russian in Ukraine now? Personally, I can say that if I say “I come from Russia, I don’t want anything to do with it and I ask to be expelled from the Russians”, then, in principle, there are no questions at all.

— Many people perceived the uprising in Donbas as some kind of alternative. As a result, one of the leaders of the National Bolsheviks went to jail on the way out of the region, and the party was banned from carrying out any agitation pretty soon. Communists from Borotba ended up in the basement, and the commander of the “Ghost” brigade, who flirted with socialist rhetoric, died under rather strange circumstances, as did other field commanders.

Leshy:

— As for my attitude, I have been involved in these events since Maidan. Therefore, from the very beginning, I treated this epic as a project of the Kremlin regime. Although, of course, I am also aware that the history there is not black and white and not so unambiguous. Of course, there was a certain social conflict with deep roots.

Movchan:

and the «Ghost» Battalion.

Well, in the same way, one should realize that in reality they are just red conservatives who are nostalgic for the Soviet Union, but who have nothing to do with today’s progressive leftist agenda.

Leshy:

— For me, winning — is first and foremost the military defeat of Putin’s army and an uprising in Russia. According to my dream, this should cause our long-suffering Russian society to stir up all this, it will stand on its feet and throw off the crap we have been forced to carry for more than 20 years. I sincerely hope so. This is one of the most important reasons why I am here at the front. I want to personally contribute to the defeat of this monster, which has now spilled out so horribly over the border of the Russian Federation and which, I hope, will break its teeth here.

Movchan:

— Well, for me personally, when I think of victory, I rather think of a new phase of the struggle. That we will finally be able to stop fighting this external enemy that we are now forced to fight, whether we want to or not. After that, we will be able to switch to all these internal contradictions, which I, as a person of leftist views, usually find it necessary to talk about at all times. That is, social issues, economic issues. And there will be a lot of them!