Confederation or Empire: the key question of the war in Syrian Kurdistan

In the hustle and bustle of the constant flow of disturbing news from Northern Syria, the essence of the ongoing conflict is often lost. I would venture to suggest that in the popular mind the current confrontation remains a “war between Turks and Kurds”. However, the real demarcation line of the warring parties is not at all along national borders.

For many years, a large-scale battle between two projects of the future has been unfolding in Kurdistan, i.e. in the territories where Kurds constitute the ethnic majority. Today’s round of bloodshed is one of its episodes.

Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan and his state machine epitomize the political project of “neo-Ottomanism,” a modern interpretation of the political maxims of the Ottoman Empire. The neo-Ottoman paradigm implies centralization of power in the hands of the president, expansion of the Turkish state’s influence over its neighbors in the Middle East region, and an appeal to Islam as a political value and a factor that can unite people across ethnic barriers. All of these features are prominently displayed in Erdogan’s policies.

On the other side of the front line are supporters of “democratic confederalism. The author of this concept is the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Abdullah Ocalan, who developed it in the mid-2000s while in Turkish prison. The PKK took it as the basis of its program. Since then, the creation of a self-governing autonomy has replaced the former goal of building a socialist nation-state of Kurdistan among the party’s objectives.

Democratic confederalism severely criticizes the state as an apparatus of oppression, coming closer in this aspect to anarchism. Without becoming a state, autonomy should develop a system of direct people’s power through councils. The ideology of the PKK, to an even greater extent than neo-Ottomanism, seeks to overcome national disunity, declaring as its goal the creation of an equal confederation of the peoples of the Middle East. A special place in its ideological arsenal is given to gender equality. Thus, the modern PKK cannot be equated with the classical national liberation movement or, even less so, with Kurdish nationalists. “Democratic confederalism severely criticizes the state as an apparatus of oppression, coming closer in this aspect to anarchism.

At the same time, there are opinions about both sides of the conflict that behind the ideological signs there is corruption and the struggle of two groups of the political elite for power. Undoubtedly, the element of “power struggle” is indeed present to a certain extent. But in the course of two trips to Kurdistan and intensive communication with the participants of the Kurdish movement in Russia, I was convinced that among them prevail people who sincerely strive to realize the ideas of Abdullah Ocalan. The practice of this movement also testifies to the same.

The struggle between the Confederacy and the Empire takes different forms in different territories. The Peoples’ Democratic Party acts as the legal wing of the Confederalist movement in Turkey. DPP deputies hold 59 seats (about 10%) in the Turkish Majlis. During the brief period of truce and peace process between the PKK and the government in 2013-2015, under the patronage of the DPP, Confederation institutions: assemblies and committees were established in the Kurdish regions of Turkey. Since 2015, when hostilities resumed, all the established structures and the DPN itself have come under a barrage of repression.

Organized in the spirit of neo-Ottoman expansionism, the Turkish state pursues the enemy and extends military control over its own borders. The mountains of the far north of Iraq became the stronghold of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and the center of its infrastructure back in the 1980s. Today, several permanent military bases of the Turkish army are located in the Kurdish part of Iraq to fight PKK guerrillas. On Iraqi territory there have been repeatedly carried out major ground and air military operations of Turkey. The latest one to date is in May 2019.

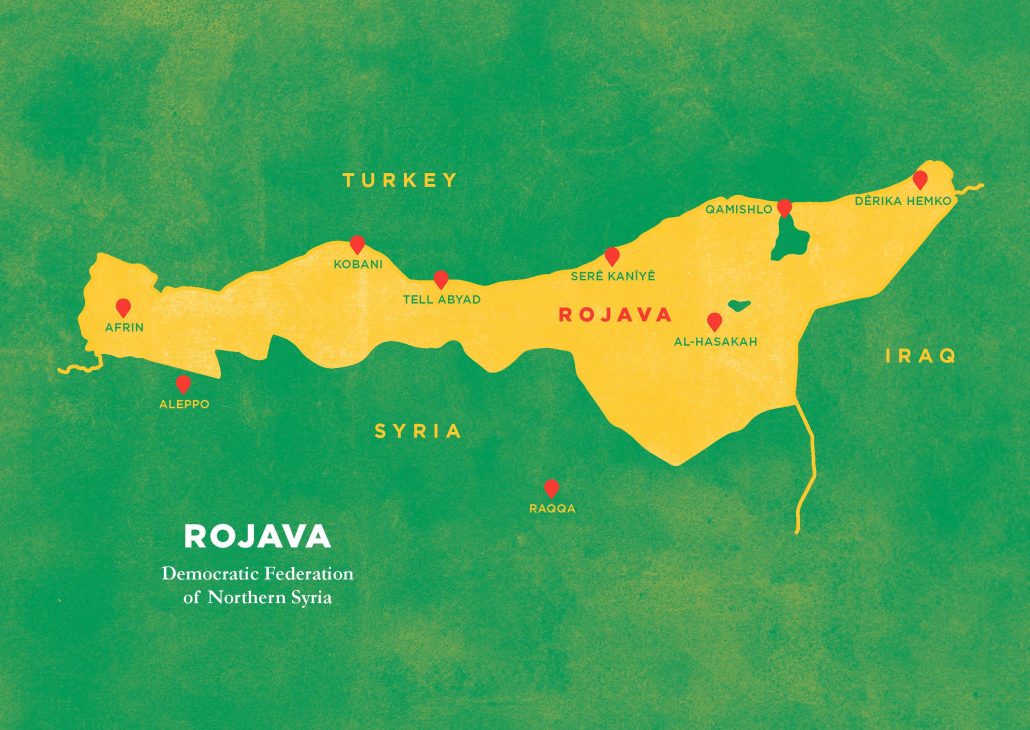

Rojava occupies a special place in this dynamic panorama. The region, home to more than four million people, was the biggest test case of the Confederation project. In the summer of 2012, Kurdish revolutionaries ousted the administration loyal to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and then organized a defense and successful counteroffensive against the Islamic State with the support of the International Coalition.

Parallel to the armed struggle for existence, a large-scale social construction was launched in Rojava: self-government bodies, including local councils, cooperatives, and women’s organizations were established.

The People’s Self-Defense Units (YPG) are the core of the autonomy’s self-defense, and the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Movement for Democratic Society (TEV-DEM) are the engine of social transformation. Formally, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party has nothing to do with it. However, it was the KRG cadres who organized all these structures.

In addition to the practical and far from successful realization of its political project, Rojava has become an important resource and infrastructure base for the PKK. In particular, the autonomy became a vast recruiting ground for new cadres of the organization.

Rojava is thus both a symbol of the Confederation concept hostile to the Turkish government and an important element in the PKK system. This is the reason why Erdogan is so determined to wage war in the region, first with the attack on Afrin in the winter of 2018 and now with a full-scale invasion of the heart of the autonomy’s territory. “The new round of war has already caused an exodus of at least 130,000 residents from the territory of the supposed ‘security zone.'”

Closely related to the invasion is Erdogan’s plan to “return” Syrian refugees to their country by moving them to a “security zone” to be established on the ruins of Rojava. Refugees are planned to be used as tools of the neo-Ottoman project as part of this idea. The Turkish president wants to “dilute” with them the Kurdish population of the region, with whom the PKK is popular. The new settlers, Sunni Arabs, are expected to be hostile or, at worst, indifferent to the Confederation movement.

The Turkish government has nominated the “Syrian National Army”, which united a number of Islamist groups under Ankara’s patronage, to play the role of self-appointed spokesmen for the political will of Syrian Sunni Arabs. Today, together with soldiers of the Turkish Armed Forces, they are “clearing space” for a major change in the demographics of the region. The new round of war has already caused the exodus of at least 130,000 residents from the territory of the supposed “security zone.

Interestingly, in Turkey itself, activists of the Peoples’ Democratic Party supported Syrian refugees. In particular, they organized additional educational activities for children who were only provided by the state to attend general school. I know of at least one such example from the city of Mersin. “Whatever the outcome of the current stage of the Syrian crisis, the struggle between the confederalist and neo-Ottoman projects will not end there.”

Confederation or Empire? There is a third answer to this debate. Hafez al-Assad and then his son, current President Bashar, built Syria as an Arab nation-state. Backed by massive support from Iran and Russia, the government has managed to regain control over large parts of the country. Faced with an attack by the technically superior Turkish army, Rojava politicians were forced to conclude an agreement with Damascus, on the basis of which Syrian army units entered the region. There is no doubt that Bashar al-Assad would like to regain control over this part of the country as well.

Whatever the outcome of the current stage of the Syrian crisis, the struggle between the confederalist and neo-Ottoman projects will not end there. The confrontation has long since spilled beyond Turkey’s borders and changed the political map of the Middle East. Both the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and its associated movements have the resources and will to continue this conflict.

It is no exaggeration to say that the political program of the PKK offers a new solution to the old problems shaking the region. First of all, the problems of national inequality and inter-ethnic confrontation. Will these ideas be able to withstand the military might of NATO’s second strongest army and spread to new territories and national groups? This question will be answered in the near future.